Skoug's Candy Company

126 W. 9th. 1909 - 1924

1001 E. 8th 1924 - 1960

1001 E. 8th 1924 - 1960

In 1903, Anton Skoug had a little candy and ice cream stand in the Cataract Hotel at the northwest corner of 9th and Phillips. It wasn’t going well. His brother, Emil, was working at Will Rounds’ clothing store in the Boyce-Greeley block at 11th and Phillips. Anton closed up his stand and packed it up for another attempt in Watertown. At the same time, Emil moved to Watertown to run the clothing department of a department store there.

In 1904, Carl W. Anthony opened his new store, the Boston Candy Kitchen, in the Hollister-Beveridge block at 126 W. 9th. Anthony’s store had sodas, candies, ice cream, light lunches, and tea rooms in which to enjoy them. His Ambrosia chocolates, made daily, were the talk of the town. It’s unclear what went wrong for Anthony, but in 1906, Anton Skoug, who had moved back to town, took over the Boston Candy Kitchen and remodeled. The new store would be called Skoug’s Candy Company. Skoug’s had much of the same stock, but Anton would add his own touch to the confections sold here. From the beginning, Skoug promoted the purity, freshness, and quality of his product. He was also sure to advertise with large promotions for Easter, Christmas, and Thanksgiving. The lunches that were served each day kept the lights on, but beautifully-packaged candies were big profit-makers. By 1914, business was good enough that Emil joined Anton in the business.

In 1904, Carl W. Anthony opened his new store, the Boston Candy Kitchen, in the Hollister-Beveridge block at 126 W. 9th. Anthony’s store had sodas, candies, ice cream, light lunches, and tea rooms in which to enjoy them. His Ambrosia chocolates, made daily, were the talk of the town. It’s unclear what went wrong for Anthony, but in 1906, Anton Skoug, who had moved back to town, took over the Boston Candy Kitchen and remodeled. The new store would be called Skoug’s Candy Company. Skoug’s had much of the same stock, but Anton would add his own touch to the confections sold here. From the beginning, Skoug promoted the purity, freshness, and quality of his product. He was also sure to advertise with large promotions for Easter, Christmas, and Thanksgiving. The lunches that were served each day kept the lights on, but beautifully-packaged candies were big profit-makers. By 1914, business was good enough that Emil joined Anton in the business.

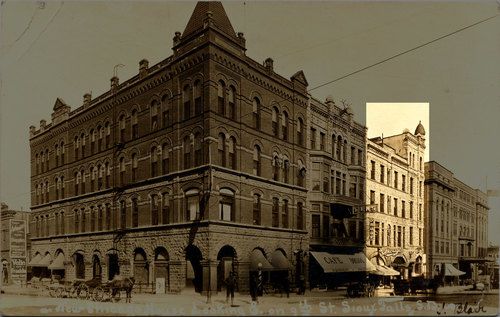

Skoug's shop, highlighted here, just east of the old Elk's Club building on the north side of 9th Street between Main and Phillips.

By 1919, Skoug’s Candy Company had a large staff, though not as large as Fenn’s, a popular candy wholesaler. A union organizer who came to town representing the Bakers’ and Confectioners’ Union demanded a strike by all union members of both Skoug’s and Fenn’s. Six workers walked out of Skoug’s and about 75 walked out of Fenn’s. The union wanted closed shops, which meant that every worker of each business would give hiring preference to union workers. The desired outcome of the strike was to earn more dues and increase the leverage of the unions locally. James Fenn told the Argus Leader that the striking workers were welcome back when the strike was over, but that he could not demand that all employees join the union. Anton Skoug said he would replace the missing staff immediately. Workers from both businesses who were interviewed said they were satisfied with the pay and working conditions provided by their employers. The strike ended when a union meeting, which was not as well-attended as the organizer had hoped, turned into a dance. After the organizer left, someone started playing a popular song of the day and a good time was had by all.

In 1922, Skoug’s started making a new confection called, at the time, an Eskimo Pie. This was the first time melted chocolate was magically adhered to a cube of ice cream on a stick, and America loved it. It was invented the previous year by Danish immigrant and candy store owner Christian Kent Nelson, who patented and franchised the product. Ice cream manufacturers could pay for the right to produce the product. Skoug’s sold them for 10¢ each.

By 1923, Skoug’s had been in the wholesale business for a while, but had continued to maintain a storefront. A new $35,000 66 by 80-foot manufacturing plant was being built at 1001 E. 8th, and during that process, a decision was made to shift Skoug’s business model to manufacturing only. You could still get Skoug’s candy and ice cream, but you’d have to buy them in stores that carried them. The plant was finished by July of the following year. Salesmen were pounding the pavement in a 75-mile radius for new buyers.

In 1922, Skoug’s started making a new confection called, at the time, an Eskimo Pie. This was the first time melted chocolate was magically adhered to a cube of ice cream on a stick, and America loved it. It was invented the previous year by Danish immigrant and candy store owner Christian Kent Nelson, who patented and franchised the product. Ice cream manufacturers could pay for the right to produce the product. Skoug’s sold them for 10¢ each.

By 1923, Skoug’s had been in the wholesale business for a while, but had continued to maintain a storefront. A new $35,000 66 by 80-foot manufacturing plant was being built at 1001 E. 8th, and during that process, a decision was made to shift Skoug’s business model to manufacturing only. You could still get Skoug’s candy and ice cream, but you’d have to buy them in stores that carried them. The plant was finished by July of the following year. Salesmen were pounding the pavement in a 75-mile radius for new buyers.

In 1935, Skoug’s and another local dairy called Bridgeman-Russell merged to form a new company named Dairyland Creamery Co. Anton Skoug stayed on as president of the new firm, retiring to Arizona in 1947. Emil left Sioux Falls in 1936 for Glendale Californa. Anton died in 1961, Emil in 1962. Dairyland went on until 1952 when it was acquired by Foremost Dairy. In 1960 Foremost was forced to sell off companies they acquired in 1952 and '53, as they'd bought out all their competitors. The Skoug's name lives on in the form of collected tin signs and the occasional sighting on the side of a building revealed by the destruction of its neighbor, or in an old newspaper.